Love consists of this: two solitudes that meet, protect and greet each other.

— Rainer Maria Rilke

Love consists of this: two solitudes that meet, protect and greet each other.

— Rainer Maria Rilke

तुम

बस शब्दों का जाल बुन देते हो…

सुनहरा, चमकीला

मेरा मन फँस जाता है उसमें

और इतना गहरे

कि लगता है जाल ही सच है,

जगत मिथ्या…

और जब निकल पाता है

तो पता चलता है

कि सब कुछ बदल चुका है…

आधा हिस्सा वहीँ छूट चुका है…

नहीं, इसमें तुम्हारी गलती नहीं

तुम्हें तो शायद पता भी नहीं होता…

पर किसी दिन फुर्सत हो

तो देखना

तुम्हारे आस-पास

कितने सारे टुकड़े पड़े होंगे…

मन के,

सपनों के,

कई सारी हसरतों के―

इकारस के पंखों जैसे…

शीशों के उन टुकड़ों में खुदको देखोगे

तो मसीहा नज़र आओगे…

पर वो फँसने वाला मन

शायद नहीं जानता था

कि तुम तो खुद भी

कैदी हो खुदके ही

Is your pH level 14 because your a basic bitch

…or is it less than 1 because you are a vitriolic vamp?

किरचें कुछ चमकीली-सी

वक़्त की जेब से

चुराकर लायी हूँ

कागज़ की पुड़िया में

लिपटे कुछ लम्हे हैं

थोड़ी सी कॉफ़ी है, थोड़ी सी बारिश

गुलाबी शहर की गलियों से लिए

पुराने रेकॉर्डों की आवाज़

सर्दियों की वो कहानी-सी शाम…

कुछ नए पुराने शब्द हैं

यूँ ही बातों से बटोरे हुए

सहेजे फिर हाइकु में पिरोये हुए

और इन सब से बंधा-उलझा

सम्मोहित मेरा मन ।

Pleasure is never as pleasant as we expected it to be and pain is always more painful. The pain in the world always outweighs the pleasure. If you don’t believe it, compare the respective feelings of two animals, one of which is eating the other.

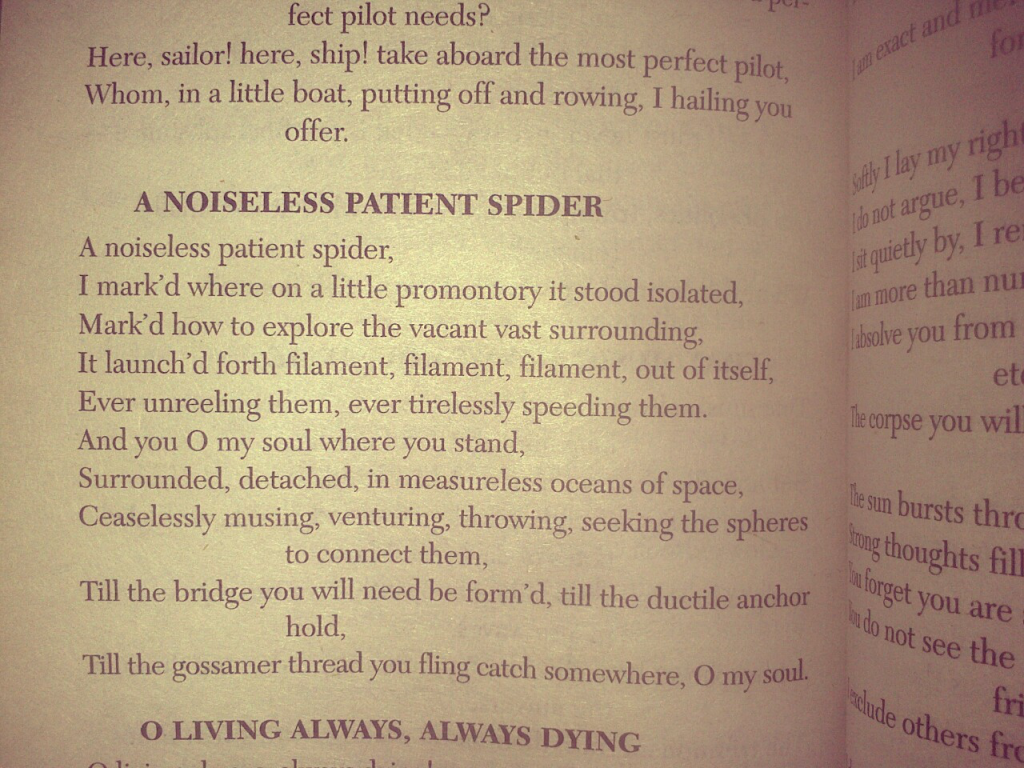

Found this in an old volume of Kipling’s short stories I read when I was about 11, and never understood. Except these lines. Must have underlined for a reason, back then.

raindrops spatter

in distant light

noiseless coins

falling on asphalt

Somewhere in the hospital

An IV drips…slowly, slowly

Each drop beginning to form

Growing fuller,

Catches the light of a lone bulb,

Becomes a luminous microcosm in itself…

Millions of molecules of magic and brightness

Travel downwards into the darkness of veins

Carried on the river of red,

Finding their target

Through a sheer instinct of fitting-in

Of close bonds

Of spatial snugness

Contained in their chemical subconscious.

And then it begins…

The intricate cascade

Of cause and effect, cause and effect

Looping in and around itself

A subcellular waltz

A delicate surge of electricity,

A tiny burst of heat,

Lightning leaps across a synapse

And a heart resumes its beat…

Throw this stale grief out with the bath water.

It isn’t worth immersing in again.

Brave face, young girl – be your father’s daughter.When the deluge leads like calf to slaughter,

shoulders slumped beneath the weight of the reign,

throw this stale grief out with the bath water.Church bells ring, well-meant promises falter.

Hold your own hands, to yourself do explain:

Brave face, young girl – be your father’s daughter.Lost on the wheel of a careless potter,

when your body turns empty subway train,

throw this stale grief out with the bath water.Soak not in this woe, stay not a squatter,

though each step may feel as if wrapped in chain.

Brave face, young girl – be your father’s daughter.Lay me down beside the flooded altar.

When at dawn, naught else but this does remain,

throw this stale grief out with the bath water.

Brave face, young girl – be your father’s daughter.

I lost my father yesterday. Sitting in a darkened room, I stare at his photograph and tell him to send me a sign. Aimlessly I pick my phone up and this poem turns up first in my feed reader.

Thank you, poet…

Thank you, dad…

That awkward moment when you start reading a Harry Potter Next Generation fanfic and the scene is the start-of-term feast and you suddenly realise that the headmaster isn’t Dumbledore anymore :(

“Poets are soldiers that liberate words from the steadfast possession of definition.”

“I enjoy talking to you. Your mind appeals to me. It resembles my own mind except that you happen to be insane.”

This rings so true right now.

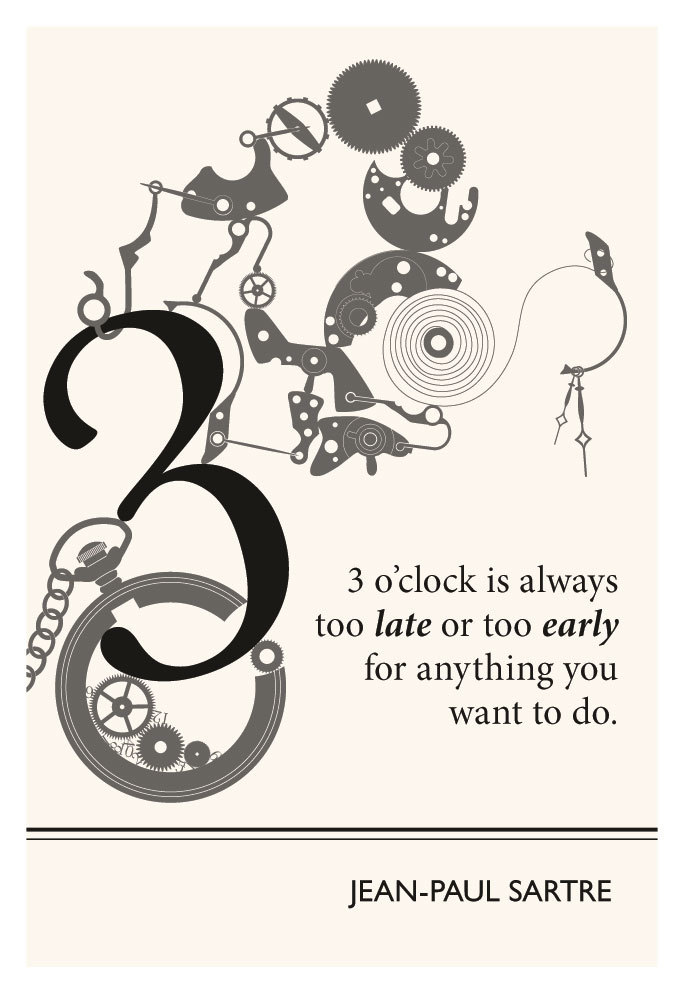

(Source: from the elegant literary poster series by Evan Robertson for sale on Etsy.)

So spread your wings and fly…

Guide your spirit safe and sheltered

A thousand dreams that we can

Still believe…

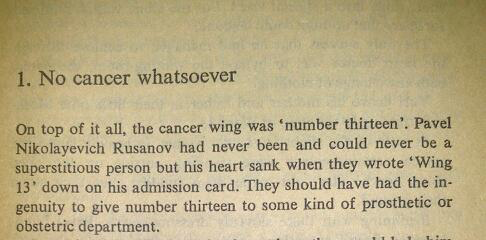

(Published in the latest issue of Dr India, a newly started medical / lifestyle magazine, my recollection of a remarkable person I met not so long ago…)

It was a rainy July morning when I first saw her. I was in the Cancer OPD, going over case histories with patients and their relatives for an epidemiological study that I was doing. A girl of only about my age, she came in, clad in a simple cotton suit, a closed umbrella and muddied sandals meaning she had walked a long way in the cold rain. There was this vague air of sensibility around her…a sense of intellect that defied her unassuming and modest demeanor. She watched her surroundings — the patients, attendants, doctors, even the three of us med students — just the way I had often found myself doing — paying attention to little details, being attuned to the slightest of changes in tones and expressions.

We all, each have a story in us. Her mannerisms seemed to speak aloud that hers was a remarkable one. I went up to talk to her, to get her case details for my study, and we ended up talking for perhaps an hour — she telling me all about the past two years of her life and her journey across the landscape of a terrible disease, often sobbing when the memories got cruel…and me being successively curious, saddened, angered at the rough hand life had dealt her, to finally being overwhelmed and amazed by her courage and resilience. There are not many people made of such strong stuff and I felt fortunate to have come across her. It was the kind of chronicle that I had previously only read in ‘Chicken Soup for the Soul’ books, and to actually meet someone who had gone though all those circumstances was a sobering experience. Here is her story. Hopefully a lot of us will derive strength from it and send good wishes and healing thoughts towards her, so that she may have a much happier life ahead.

Of course, the names have been changed to protect the privacy of the real patient and other people involved. The facts stay true, though I believe my words cannot sufficiently do justice to their poignance.

“It was dark when the train pulled in into the crumbling old station away from downtown and screeched to a halt. I got up to take my bag from the overhead rack and immediately became conscious of a deep, throbbing ache where the medical centre staff had poked and prodded so much the previous time but in the end failed to aspirate a testable portion of my bone marrow anyway. So much for their ‘aspirations’.

I’d always had a primal fear of hospitals and clinics ever since childhood. Most of it was due to the specific old gentleman, the only doctor we had in our tiny little town. He always had this slightly sour, caustic look on his face that lent extra bitterness to the horrid concoctions he made us drink as kids who were in mortal fear of him. And there was this distinctly demonic, villainous way in which he held the syringe just before plunging it deep into the quaking, trembling kid in front of him. It didn’t help my fear whenever I saw the state of the town clinic , smelling always like blood and other indefinable odors only slightly overlaid by the phenyl that they swept with, which was probably expired in any case.

And now here I was, Rekha Singh, in and out of hospitals all the time, shuttling from one to the other several times a month, often alone. What a way to cure my terror of hospitals. God surely had a twisted sense of humor.

It all started when one day, returning from fieldwork at the NGO where I worked, my friend Seema mentioned that she had to go get her hemoglobin checked. Just on an impulse, I decided to go along too. So I called home and told my mother that I would probably be a while late and she agreed, telling me for good measure not to spend too much on “unnecessary tests”.

I lived in a family that seemed to be hanging together perhaps only through an extra effort on the part of fate. My father was (and sadly, still is) an alcoholic, long since having stopped doing any gainful work. I have an older sister (obsessed with her own kids), a younger sister (obsessed with her own marriage dreams) and then a still younger brother (obsessed with, thankfully, nothing else but cricket). Mother was often irritable, overworked, and most of all, overstressed at finding herself at the centre of such demanding and in her opinion, dysfunctional individuals. No, I wasn’t spared either — I might have been the sole breadwinner of the family with my king-size monthly income of Rs 6000, but a daughter who couldn’t be home in time to cook meals and wash clothes and get married by 27 years was still dysfunctional. So we all mostly kept out of mom’s way. The only days I felt her relaxed were the ones on which I handed her my paycheck on which we had to subsist. No luxuries for us, you see.

Not that it ever stopped me from dreaming. All through my graduation from the College in the next town I haunted the library, immersing myself in classics and poetry and books and papers of all kinds — not to just escape the sorry circumstances of home life but to actually keep myself buoyant above it all. I did an MA in Sociology. Joined an NGO for rural women. Aspired to make a difference. Life could be so much better with a little imagination and dreaming.

Anyway, back to Hemoglobin Day. Me and Seema reached the new private hospital in town and gave our blood samples. I wasn’t really expecting anything out-of-the-way, it was just a whim (and the lab tech was a really good-looking guy). Just kidding.

But the results came the next day. My Hb level was 5.

Sure, I had felt a few symptoms so far — tiredness, paleness, all that, but nothing drastic. And I had attributed it all to general blood loss — hell, half the girls around there probably suffered from it. But now there were the numbers to prove it. The doctor at the town hospital started me on iron supplements and for good measure ordered a transfusion. None of us had any idea what it would turn out to actually be. Needless to say it didn’t work. After about a month of that, my Hb levels dropped to 4. And that’s when he referred me to Jaipur.

My father and brother accompanied me here. The first time that I reached the cancer & hematology hospital, I was utterly terrified of the ambience here. The throng of frail patients in the waiting room, catheters and IV ports and headscarves to cover their loss of hair…the sad, resigned faces of their attendants, amid the rustle of inches-thick folders of their reports. I didn’t care what was wrong with me, I just wanted to get out of there.

My doctor, Dr Mehra — an enthusiastic personality in his 30s, was an island of calm in the midst of all that morbid chaos. I saw him greeting every patient by name, talking to them in their own dialect, and laying out facts with the utmost care and concern. I told him what was wrong and it was as if I could see right in front of my eyes some diagnosis starting to form in his mind. He reassured me and sent me to a nearby facility to get a Bone Marrow biopsy and more tests. He said it was just a simple test, they needed to put a long needle in and take a piece of my marrow to microscopically analyse it. But the lab turned out to be an ordeal. The procedure which was supposed to be mostly painless was terrible, like a jagged piece of glass inserted way deep into a wound and doused with acid on top of it. I screamed my way out of there and we were told that they could not get the sample and I was supposed to come back later. I decided I never would.

I went home and started on some Ayurvedic preparations by an herbal practitioner that my mother had faith in. Even with that, I needed transfusions multiple times a month. Initially, my younger brother agreed to give me blood, since he was AB+ too. After the second time, he and I got back home from the hospital to find my mother in a hysterical state. She had happened to read somewhere about blood loss in young children and from then on, prohibited my brother from giving me any. Yeah, the love for the son outweighing that for the sick daughter. Welcome to my family.

In the next months I put in requests and filled request forms myself at the blood donation centre. I was always so fatigued, so tired. Each step was like dragging my feet through a quagmire. But I could count on no support from my family. In their eyes, my monthly salary had stopped coming since I could work no more and that was my fault. When the donation centre was of no immediate help, I would take the numbers and contact the regular donors myself, going up to their doors and asking for AB+ type blood. They would say, “Sure, are you a relative of the patient?” and I would reply that I am the patient, and they would stare at me, unbelieving and confused. We would then go to the hospital, I would get transfused and go home alone. And the next month I would go door-to-door to beg for blood again, almost like the street kids came begging for food.

One day, as I was lying in the general ward, a much precious bottle of blood hooked up to my arm, I happened to notice more-than-usual commotion at the other end of the hall. I looked over to see a guy about my age lying on the cot, surrounded by anxious family members, a whole lot of them. I looked up at the IV pole and there was just a bottle of glucose being given to him, apparently after a heat stroke or something. The family was out of its wits with anxiety. The mother was crying that she doesn’t take proper care of her son. Someone was bringing biscuits, someone water, someone calling the doctor to pay a second visit just in case, and the patient’s younger sister was lovingly stroking his forehead while he slept, apparently with no complications.

Right over there, someone was being so much fussed over while getting simple glucose and here I was, alone at every stage from procuring blood to going home after the transfusion and re-heating my lunch myself. That day I felt I would die here in this hellhole with a totally estranged family if I did nothing to make myself better. I felt it would matter to no one if I died, not my hypercritical mother, my alcoholic father and apathetic siblings…but it would matter to ME, and that day, it was enough motivation for me to begin to save my own life.

I went back to Jaipur the next day and told Dr Mehra about the botched biopsy, the transfusions, and how I could not do it anymore. He very gently told me to relax, that he was going to take the biopsy sample himself. This time, it was over before I knew it.

I was diagnosed with Aplastic Anemia. All my blood-cell counts were discouragingly low. The strangest thing of all seems to be, they didn’t know what the cause was. Idiopathic, they said. That’s right, no reason. My body decided to play rogue against itself just like that, for no reason. Talk about purpose in life.

Later Dr Mehra told me it was my body’s own white cells attacking my marrow and destroying it, stripping it of stem cells that generated the RBCs. It was as if an internal vampire was drinking my blood inside my body itself, even before the blood was ready.

I took 50,000 in loan from a moneylender in the town and with no idea of how it was going to be paid back, and for the next months, I would come to Jaipur for checkup and therapy, alone on the night train, and there would be nobody at the station to pick me up. I would get an auto, go to a distant aunt’s house, the only relative I had in the city. Didn’t have enough money for guest houses / hotels and my family said it would be better if I stayed with a relative, that they cared. But obviously not enough to accompany me. There would be an old rickety chaarpaai for me in the storeroom adjoining the kitchen, and there I would sleep, the rats and mice among the groceries constantly scampering about in the tiny room and a sharp stream of cold wind blowing in from the window that didn’t close fully. I was experiencing some side-effects of my medication by then and one of them was my need to empty my bladder frequently. The bathroom was actually outside the main house, at the end of the driveway. My aunt would sometimes tell me it was occupied by another family member, even if it wasn’t. I don’t know why she wanted to prohibit me from that. I told her that due to my medications I needed it frequently but she didn’t respond. That night I woke up with an urgent need to go to the washroom and went to the door that led to it. It was locked. My aunt had expressly locked it before going to sleep. I came back to my cot and sat awake through the entire night, my muscles clenched, hands around my knees, holding it in and crying to myself. Forget health, forget family, forget the concept of love, all I wanted in that moment was access to a washroom and somebody had willfully denied me even that. What was my fault?

The next morning I would go to the hospital and stand in the free medicine distribution line to get my own medicines. I could hardly stand up, much less make way among the typical long jostling queue of patients’ attendants, managing not to faint until I got them. The man at the desk would ask me where the patient was. I would tell him it was myself and he would look at me incredulously and ask again, until the person behind me in the line would brusquely tell me to hurry up. Then I would go up to the second-floor ward and get admitted for the day and have the whole soup IV’d in. The things I did made me seem as if I were addicted to cyclosporine and what not that they were giving me.

In a way, I was. I loved the way I would feel visible, tangible improvements in my health. The medication began to work. But so did the side-effects. Over the next months I developed a lot of random infections and fevers due to my suppressed immune system. Nausea, vomiting became my constant companions. I developed severe bloating and purpura on my legs and torso as my platelet counts were still too low. Constellations of bruises and petechiae all over my body. I had excessive facial hair growth on account of the steroids, to the extent that I could not bear to look at myself in the mirror. My mother forced me to keep my face covered at all times, even indoors. Most of the time I spent shut inside my room, feeling like everything and everyone was against me, including my own body.

During those days I happened to have a pet parrot in a cage, and I would often compare my life to his. We all feel we are inside cages at some point, don’t we? In those long summer afternoons, drowsy from the potent cocktail of my medicines and with no one else to talk to, I would talk to the parrot, saying whatever I wanted, cursing my disease, lamenting my own existence, hoping it would all turn out fine…until one afternoon, it struck me that I was not as helpless as the poor little bird. I could talk about what I was going through. I could share it, could speak, even though nobody would listen. And I took the little silent bird in the cage to my rooftop and set it free, hoping it would find those of its own kind and they would somehow listen to him.

…

It has been almost a year since my treatment started, and I am in full remission now. Glad to say that the more hideous ones of my side-effects have subsided. I still have to come here to the hospital about once a month for follow-up, and everytime I come here, I am reminded of that very first time in January that I was here, terrified to death…and everytime I am greeted by the same enthusiasm of my doctor. My family remains the same way, unsupportive, cynical. Guess some people will never change. I have re-joined my job at the NGO and have met more like-minded people there and we are now working on a project involving support groups for terminal patients in and around where we live.

Throughout the course of my disease, I have discovered hidden reserves of courage and power I never knew or imagined I had. I have learned to not take anything for granted, not even the existence of your own blood. I have learned that nobody knows the outcome for sure but that doesn’t mean we stop taking our chances. I have learned that some people are just built the way they are and trying to gain their support leads to nothing else but humiliation in your own eyes. I have learned to fight for what should be mine. That some bruises never go away but you can always think of them as battle-scars. That even nasty side-effects lose their edge when you think of them as signs that the medication worked. I have now slowly been able to undo the hate I felt against my own body for turning traitor, and each and every single day I am intensely aware of the blood now flowing through my arteries — pure, unsullied, bountiful.”

Everybody has these teenage ‘phases’ you know, where one thing or the other dominates your whole psyche (or whatever passes for it at that time) totally. At the age of 15, I was in my ‘logical’ phase. Having been an avid reader since the time I could string more than 4 words together, books pervaded my life.

I’d gone through (and been done with) the Hindi comics by 8-9, read all the fairy / folk tales I could lay my hands upon (A translated omnibus of English, Egyptian, Russian, Ukrainian and Irish ones) by the time I was 10, discovered and read Charles Dickens and other major classics (abridged, though) by 13, and therefore, at 14-15, I was going through anti-war sentiments generated by Hemingway, The Diary of Anne Frank, and translated versions of post-WW II era Russian literature. Not to mention trying to understand the Rhett Butler – Scarlett O’Hara dynamics in Gone With The Wind.

I was in the ‘realism’ phase.

Then one crisp white-cloud green-trees winter day in late 2005, sitting on the sun-warmed gray stone bench at the school garden in recess, a friend asked me if I had liked Harry Potter.

I actually smirked at her.

“I haven’t even read it. And neither do I wanna. How could all these people be so interested in that unreal magic stuff?? Come on, how could you be??” I asked another girl to back me up. She was (and still is) one of the most practical people I’ve ever met, and at that time, she shared my there-is-so-much-real-bad-stuff-in-the-world feelings, courtesy Anne Frank.

“I’m in love with Harry….” Ms. Practical sighed. I rolled my eyes at her.

“It’s kid stuff – reviews say flying cars and magic wands and such…” I scoffed.

(Gawd…I was snobbish about things back then ! :D)

“Just read it once ! come on, take it as a challenge that you can still read kid stuff.” She said.

I reluctantly took the copy of Goblet that she was handing me, and turned the first page in the next free period. Fell in love with Cedric somewhere along the way ;) and didn’t stop till I’d gone through the book. The plot of what I had called kidstuff turned out to be amazing, the characters deep and complex, even the side ones…the settings totally believable, the narrative tight with no loose ends, the context and literary motifs and symbolism beautiful.

This memory of that day is still crystal-clear, Pensieve-fresh. THAT was my first ever lesson in not to be prejudiced about anything. And believe me, I’ve remembered it.

The rest, as always, is history. I read the fourth first and then went back to 1st through 6th. Better late than never. And like most of us, for me the books took the status of an epic.

The movies never did compare to the books and imagination, but then again, to see that magic brought alive on-screen has always been enchanting. (Interestingly, in both the concluding movies, my favorite sequences remain the ones which were actually NOT in the book — in 7 part 1 : the Harry and Hermione dance, for which they managed to find the most perfect song that there could be for the situation…and in 7 part 2 : the different-from-the-book but still beautiful cinematography and execution of the young Lily-Snape memory…the only bright, sunshiny moment in the dark, brooding movie.)

Nick Cave’s accompanying song to the fugitive friends’ fleeting moment of normalcy goes like

Hey little train! We are all jumping on The train that goes to the Kingdom We’re happy, Ma, we’re having fun And the train ain’t even left the station Hey, little train! Wait for me! I once was blind but now I see Have you left a seat for me? Is that such a stretch of the imagination? Hey little train! We are all jumping on The train that goes to the Kingdom We’re happy, Ma, we’re having fun It’s beyond my wildest expectation…

These lines, with their strong suggestion of the scarlet steam engine that ferried hopeful kids to a magical castle, were the actual point where my wistfulness began.

The very last installment has been out now, and the reason I’m writing this all these days later is that only after watching 7 part 2 for the second time, it has actually sunk into me that this is it. :(

There’s going to be no more of the books, no more of that fantastic saga….no matter how many times the die-hard fans amongst us might re-live it over and over again.

It’s a deep nostalgia unlike any other. The characters in the story grew, and we grew alongwith them. They say that the beliefs and impressions of childhood go a long way in shaping us. Through the books, vicariously but still in a very tangible way, we levitated feathers (among other things :P), extracted thoughts, mixed the most amazing of potions, roamed secret passageways, fought trolls and giant spiders and dark lords, charmed objects to our will (My favorite being Hermione’s extended-storage beaded bag ! :) ), sneaked around in the restricted sections of library…and at the end of the day there always was a warm, cozy, firelit, deep-red-and-gold common room full of squashy armchairs to relax and hang out with friends.

We learnt that ‘it is what you choose to be that counts’. We faced our fears and discovered our Patronuses — our strengths. We imbibed bravery, boldness, friendship and courage.

And even though the closure, especially on screen, was very dark and somber in its atmosphere and mood…permeated by the bête noire…it was a fitting end to a classic.

And so, here’s to a most beloved element of our adolescence…written in Everlasting Ink upon our hearts and minds —

For unveiling an exquisite new world and characters that we virtually became friends with…

For being a lesson for people like me to not have any prejudices…

For enabling us to say that we grew up with what would definitely be a classic for the coming centuries of children…

For giving whole new definitions to mundane words and everyday things…

For making all of us believe that at least a little bit of magic can exist in everything…it’s all upto how you perceive it.

After all, all of us are better for keeping the magic alive in our lives.

And therefore, We Solemnly Swear That We Are Up To No-Good !!

:)